William Lester Faurot - Civil War Soldier

Where William was born is something of a mystery. In his genealogical search, J. Michael Joslin, William’s third cousin, three times removed, found no less than four possible places of birth: New York, Canandaigua, Ontario, N.Y., Michigan, and Plymouth, County of Wayne, Michigan. The last might be the most likely because an affidavit signed by Ruth Dean stated that she was “personally present at the time and place … “ Ruth is adamant that her memory was accurate because she remembered that the next day was “Town meeting.”

We do know with certainty that William was born on April 3, 1842 to Clement Wilder Faurot and Hannah Gulick Faurot and that he had four siblings: Polly Jane, Wealthy Anne, Mehitable and John. Both William and his father were boot and shoemakers. This is reflected in one of William’s letters in which he very specifically details what he wants in the new boots that he requested his father make for him and another when he rather proudly tells his father that some of his fellow soldiers offered to purchase the shoes he was wearing, right off his feet. It is quite possible that William’s boots were taken from him by a Rebel soldier after the surrender at Athens, Alabama.

The Faurot family was living in Fayette Township at the outbreak of the Civil War. William volunteered for the 18th Michigan Infantry at Jonesville on August 5, 1862. This was the infantry that was recruited by Henry Waldron at the request of President Lincoln. They encamped and trained at Lewis Emery’s farm to the east of the city of Hillsdale.

Aunt Leutticia Faurot, wife of watson

Mike Joslin summarized the events leading to the capture by the Confederates of William and others in both the 18th and the 102nd Ohio. He based his account on “History of the 102d Regiment, O.V.I.” by George S. Schmutz and “The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal State, 1861-1865 - Records of the Regiments in the Union Army - Cyclopedia of Battle - Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers.”

This is Mike’s account:

On Sept. 24, 1864, 216 officers and men, including William Lester Faurot, and 195 men from the 102nd Ohio, were sent from Decatur, Alabama, via train, as a detachment to protect the road and reinforce the garrison at Athens, Alabama. The train was forced to stop a few miles from the garrison due to a break in the rails. When they disembarked, they were attacked by overwhelming forces under the command of Confederate General Nathan Beford Forrest, consisting of approximately 4,500 men. The detachment fought valiantly for nearly five hours, continuously moving in the direction of the garrison in Athens. They incurred considerable losses, yet causing even more losses to the Confederate forces. When they arrived within 300 yards of the garrison, they discovered that the Union forces there had already surrendered and the garrison was in the hands of the Confederate forces. They were left with no other option than to surrender. As a result of the battle at Athens, Alabama, the 18th Michigan had 10 killed in action, 3 wounded in action, 10 missing in action and 5 officers captured but later paroled.

Thirty-four of the detachment of the 18th Michigan were taken to Andersonville Prison in Georgia. The remainder of the prisoners were taken to Cahaba Prison in Alabama. Some of the Andersonville prisoners were later transferred to Cahaba.

In early March of 1865, as a result of the spring thaw, the Alabama and Cahaba rivers flooded, and as a consequence, Cahaba Prison was entirely flooded. At first, the prisoners were not allowed to seek high ground and were forced to suffer in the cold flood water, but later arrangements were made to transfer them to Union camps outside of Vicksburg, for exchange and parole. Included were 260 men from the 18th Michigan. However, the war ended, and the system of exchanges and paroles came to an end. They were to travel via steamship to Camp Chase, Ohio, and then to return home. On April 24, 1865, they, along with many other soldiers and civilians, boarded the steamship Sultana. The Sultana was badly overcrowded. It left Vicksburg, but made a stop at Memphis, Tennessee. Around midnight of April 26th, it once again got underway. In the early morning hours of April 27th, a few miles north of Memphis, the boilers of the Sultana exploded. Casualty numbers differ from story to story, but nearly 1960 died that night, including 71 members of the 18th Michigan, killed in the explosion or drowned. William Lester Faurot was among those that perished, his body was never recovered.

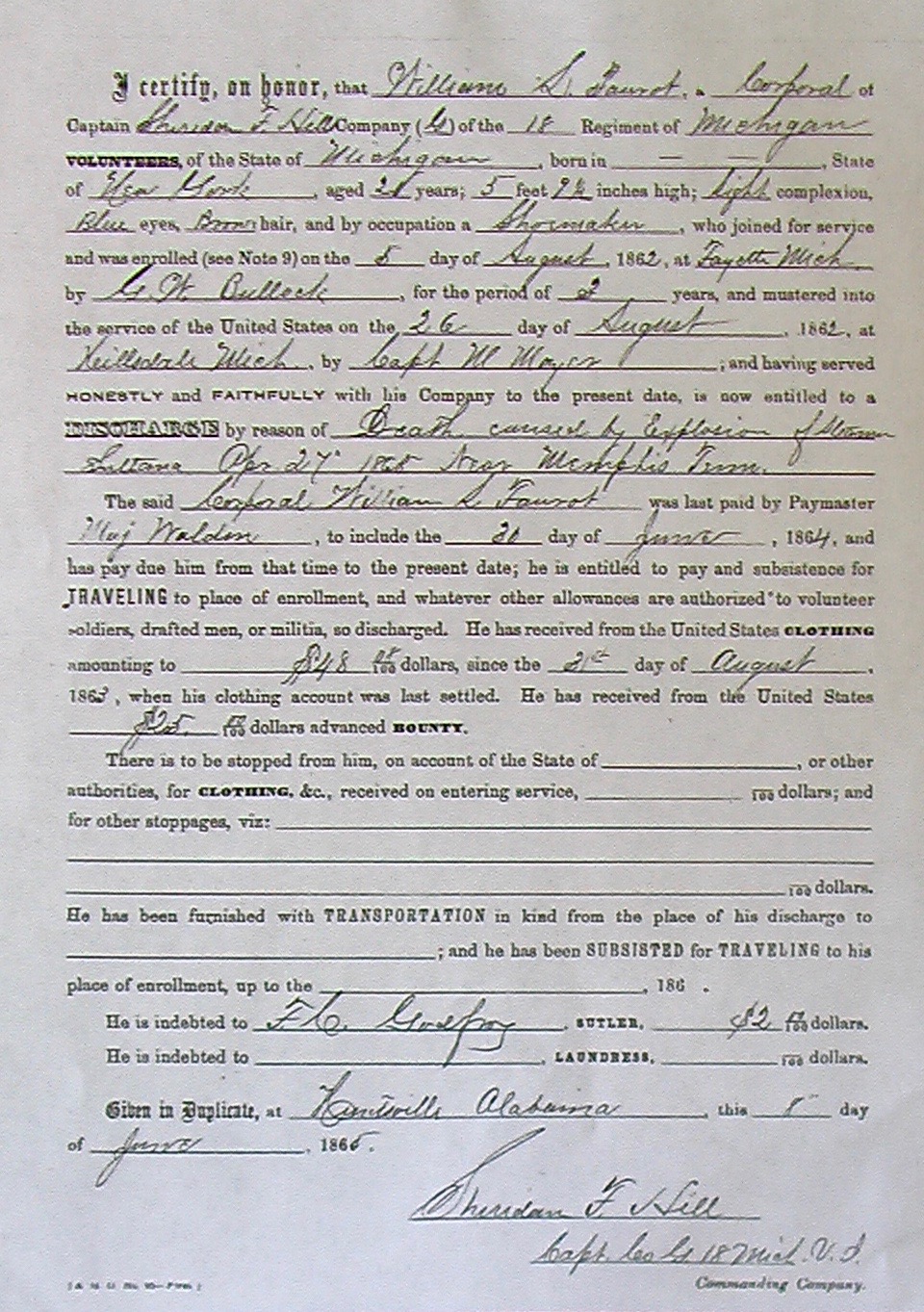

THIS WAS PROBABLY PART OF THE ATTEMPT BY WILLIAM'S PARENTS TO RECOVER THE MONEY OWED WILLIAM

William’s parents, Clement and Hannah, were left to face the battle of collecting pension funds due them as William’s parents. His pension documents are considerable in number, including affidavits from Hannah Faurot, relatives and many neighbors. She had first filed on Sept. 24, 1880. It appears it was rejected on Oct. 2, 1880. On Mar. 28, 1885, a second application was filed. Her attorney, John L. Ransom, submitted the second application for admission on May 26, 1887. On May 28, 1887, it went before a Board of Review and was approved. On June 6, 1887, a certificate was issued, then sent to Hannah on June 21, 1887. It was payable at Detroit Agency. Apparently it was retroactive, as it showed the rate per month at $8.00 commencing on Sept. 24, 1880, then increasing to $12.00 a month from Mar. 19, 1886. Further, on April 21, 1868, she was paid the $100.00 bounty due her son, William Lester Faurot, for his enlistment.

J. Michael Joslin and JoAnne P. Miller

J. Michael Joslin published a book about the 18th Michigan entitled I Fear We Shall Never See Home Again. He valued his foray into historical fiction as a way to help himself imagine what his ancestor experienced. In correspondence with JoAnne Miller, Mike contemplated what he had learned about William Faurot both factually and emotionally. Here are Mike’s thoughts:

When I learned about my ancestor and learned that he died as a result of the Sultana disaster, and more so that his body was never recovered, it affected me emotionally. My emotions piqued, even more, when I realized that most of those soldiers on board the Sultana, had participated in and survived battles, then suffered greatly in Cahaba and Andersonville prisons. After surviving all of that, I had no doubts that once they boarded the Sultana, that describing the joy they must have felt in the knowledge that they survived the worst that life can throw at them, and then, for many of them, their joy, and their lives, ended the moment the Sultana exploded. How terrible it must have been, as they stood on the deck of the Sultana, watching the fire approaching them, to have to make the choice between drowning, or being burned alive. I just knew I had to somehow give voice to William, and some of the others. By the way, you will notice that I only used the first names of the other four Coldwater boys. They were all based on actual members of Company G, but I had no idea whether or not there are living descendants of those four, and if they are aware of their ancestors. They might object to some of the actions or thoughts of their ancestors, "...Oh, he would not have done that," or "He would not have thought that." The fact is, it is possible that if anyone were to really want to know who they were based on, they could look at the roster for Company G, and figure out the real last names of Eddie, Charlie, John, and Jason.

Whoever reads the novel, I hope that perhaps one day they will contact me and tell me what they thought of my description of the battle at Athens, the conditions at Cahaba, and my depiction of that horrible event on the Mississippi River. It is the latter that I hope I portrayed in a way that will make the reader feel that they themselves were there and experiencing what those soldiers and civilians experienced. I once told Gene Salecker that I was concerned about whether or not I could adequately depict what happened the night of April 27, 1865. In Chester Berry's book, Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors, one survivor, A.A. Jones wrote "My God! My blood curdles while I write, and words are inadequate; no tongue or writer's pen can describe it." After I read that, I became concerned that I could even come close to depicting the horrors of that night. "If Mr. Jones felt that it was impossible to describe those events, what makes me feel that I can?" I reread that chapter several times, and on more than one occasion I either added something that I felt was important or restructured sentences or paragraphs. The length of that chapter changed dramatically by the time I was done. I still feel that I could have done better. When I write about people who have long since passed, I find myself wondering what they think about what I wrote. "Did I tell it correctly? Did I even come close to describing what they experienced? Is William sitting there, up in heaven, trying with all his might to have me hear him say 'I never said that,' or 'I didn't do anything like that, nor would I have.' I have no doubt that when my time comes, I may well be met by William and some of the others. That will be when I find out for sure if I got it right.

If you would like to read William's early letters home CLICK HERE

If you would like to read the story of the 18th Michigan Infantry CLICK HERE.

If you would like to read the tragic story of the Sultana CLICK HERE.