Mail Pouch Tobacco Barns

If you have a new product, you need to bring it to the attention of possible customers. In the late 19th century, long before billboards, barns afforded an opportunity for manufacturers to convince the public that they needed what the company was selling. This was especially true in the Midwestern and Southeastern United States.

The “godfathers” of barn advertising were the Bloch brothers of Wheeling, W.Va. In 1879 they had a dry goods store on Main Street, and as a side hustle they made cigars in a loft above the store. They ended up with a lot of clippings left over and developed a side hustle to their side hustle. They packaged up the clippings to make a new kind of chewing tobacco, using different flavorings such as molasses and licorice. That took care of a way to use their cigar leftovers. Then they needed a catchy name for their “chew.”

At that time the people of Wheeling would line up along the banks of the Ohio River for the highlight of the day: the arrival of the mail on a riverboat, which came in “mail pouch” bags. That name—and the good feeling it gave the observers—inspired the Blochs. They borrowed the name and called their new product Mail Pouch Tobacco. Their ploy worked and sales were good. Their product received another boost from the industries of the Ohio Valley. Many local men were employed in steel mills, coal mines and in oil and gas fields. Smoking was common and highly addictive, as we know today. The men couldn’t smoke at work for obvious reasons. But they could chew when the craving hit, and many chose Mail Pouch Tobacco.

A major flood in 1886 surged through the Blochs’ dry goods store and destroyed their entire inventory. The cigar and chewing tobacco part of the business, on the second floor, was undamaged. The flood was the impetus for the Blochs to forget about selling dry goods and to move the manufacturing of their tobacco products to a sugar mill on 40th street.

Jess Bloch, a second generation Mail Pouch Tobacco owner, came up with the idea of advertising on barns along highways in the early 1900s. Manufacturers approached farmers with an offer they couldn’t refuse. Painted barns lasted longer because the paint helped to maintain the integrity of the wood, so it was advantageous to the farmer to paint his barn. The Mail Pouch Tobacco company would paint a farmer’s barn without cost to or effort by them. Then the advertisement would be added. At first, the Blochs paid the farmer with an annual subscription to the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s or Life magazine. Later they were paid a dollar or two each year (worth $30 to $50 dollars today). The product would be advertised on one or two sides of their barn, and many of the barns and their advertisements were repainted every few years to keep the sharpness of the lettering.

Mail Pouch Tobacco barns became part of the landscape of rural areas. By the 1960s some 20,000 barns in 22 states displayed Mail Pouch advertising, with the greatest number in Ohio. Most of them were painted by Harley Warrick of Belmont County, Ohio, who began his barn painting career after World War II. First painting the background color on the barn, he and other “wall dogs” would then hand paint “CHEW MAIL POUCH TOBACCO – TREAT YOURSELF TO THE BEST” in yellow or white. Sometimes the words had a thin vertical blue border on the left and right.

Harley Warwick did his painting totally alone. He anchored a sling on the side of the roof, sat on it and then adjusted it to lower himself as he painted the advertisement from top to bottom. He estimated that he spent about six hours on each advertisement, and he said that he began each one with the letter E in CHEW. Other wall dogs included Mark Turley, Don Shires and Dick Green. Sometimes the painter would leave his initials and the date on the blue border or near the roof. In 1992 Harley Warrick retired, and the current owner of Mail Pouch Tobacco, Swisher International Group, stopped using barns to advertise their product.

During the Johnson Administration the first lady, Lady Bird Johnson, was a woman ahead of her time who was aware of the importance of making choices that would limit the negative impact of humans on the earth. However, she’s best known for championing the Highway Beautification Act of 1965. That act limited the number of roadside advertisements. Notably, Mail Pouch Tobacco barn signs were excluded because they were deemed historic landmarks.

Hillsdale County had its own Mail Pouch Tobacco barn. It stood on M-99 between Hillsdale and Jonesville in the area purchased by Meijer for a new store. Along with many other county residents, Hillsdale County Historical Society Board member Morgan Morrison was concerned about what would happen to the barn, and he contacted Meijer. Within a remarkably short amount of time, Meijer had carefully disassembled the side with the Mail Pouch Tobacco advertisement, numbered the boards and transported them to the Poorhouse complex … without charging the Society.

The area where the Poorhouse stands now has four buildings, each with its own focus. The Barn Museum was built to house the 1931 Seagrave fire engine. It has given us the space to display the many treasures we have been given and that had to be stored in the Poorhouse basement. The Poorhouse is now set up as a mid-1800s house might have been. Besides a place to sell baked goods, the General Store displays some wonderful artifacts that would have been found in a general store of the same time period. With those buildings in good shape, we can turn our attention to the old barn. With a generous bequest and a large grant from the Hillsdale County Community Foundation, we have the seed money to stabilize and weatherproof it so we can display the Mail Pouch Tobacco sign on the inside to preserve it for the future.

JoAnne P. Miller

The Rest of the Mail Pouch Tobacco Story

Shortly after the Hillsdale County Historical Society set in motion the acquisition of the Mail Pouch Tobacco barn siding, we received a donation and letter from Ellen Zienert. She said, “Thank you so much for preserving the Mail Pouch Tobacco sign. It was on the side of my husband’s family’s barn. Please record this donation in memory of the Baker Family - Ralph, Betty, Laurel (Null), Mark and Scott.”

Then, at the 2024 Hillsdale County Fair, Tom Marshall, a Baker family descendent, added to Ellen’s story. There was a house that stood where WalMart is now. It was built in the latter part of the 1800s as a hotel. Floyd Baker, who was a farmer, purchased it around 1921. It was an enormous house and several family members lived there over the years. Floyd died in 1961.

Tom Marshall also sent us additional information about the Baker family. Clark Baker threshed for area farmers. He was the one who agreed to let Mail Pouch Tobacco advertise on his barn. In addition to Floyd and Alger, his two sons, Clark Baker had two daughters, Aileen and Hazel. Floyd and Stena had five children: Glenwood, Herold, Lyle, Thelma (Tom’s grandmother) and Marjorie. None of Floyds’ children ever farmed. Glenwood was the executor of Floyd’s estate and arranged the sale of the farm and property. Clark’s second son was Alger, and he and his wife, Minnie, had five children as well: Ross, Ruth, Ralph, Carl and Doris. All three of Alger’s sons were farmers. Ralph, the middle son, bought Clark’s original farm and he and his son, Scott, farmed it. Their family sold it to Meijers.

floyd and stena baker, great-grandparents of Tom marshall

Clark Baker on his Baker steam engine tractor during threshing

Clark and his two sons, Floyd and Alger, used to do most of the threshing in the Fayette, Allen, and Hillsdale townships

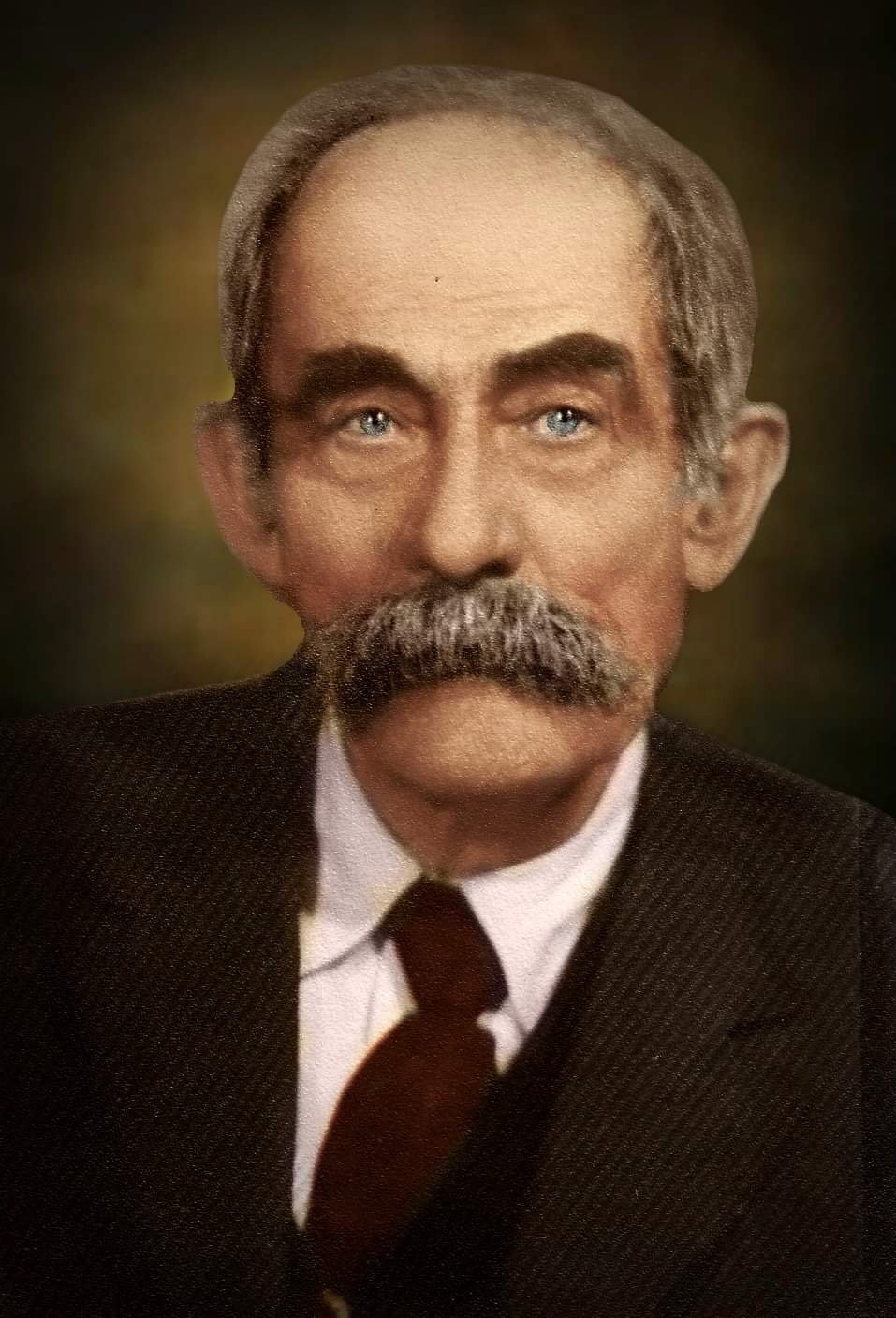

clark baker

Clark Baker, who threshed for the area farmers, agreed to let Mail Pouch Tobacco, paint the barn that stood on land that is now the Meijer’s store. Clark’s son, Ralph Baker, along with his son, Scott Baker, bought the acreage and continued to farm.

Cool, huh?