The Horseless Carriage

By the late 1800s personal transportation meant your horse, the blacksmith who kept it shod, and numerous livery stables where you could board it or rent one if necessary. But then the challenge of avoiding horse poop when crossing the road was complicated by the additional challenge of dodging new-fangled horseless carriages, the first of which was sighted in Hillsdale on October 3, 1899. It wasn’t a seamless transition. The only rule of the road was the vague assumption that you stayed to the right. Speaking from observation, the newspaper cautioned the "autoists" that "accidents to pedestrians and people in carriages are very possible.”

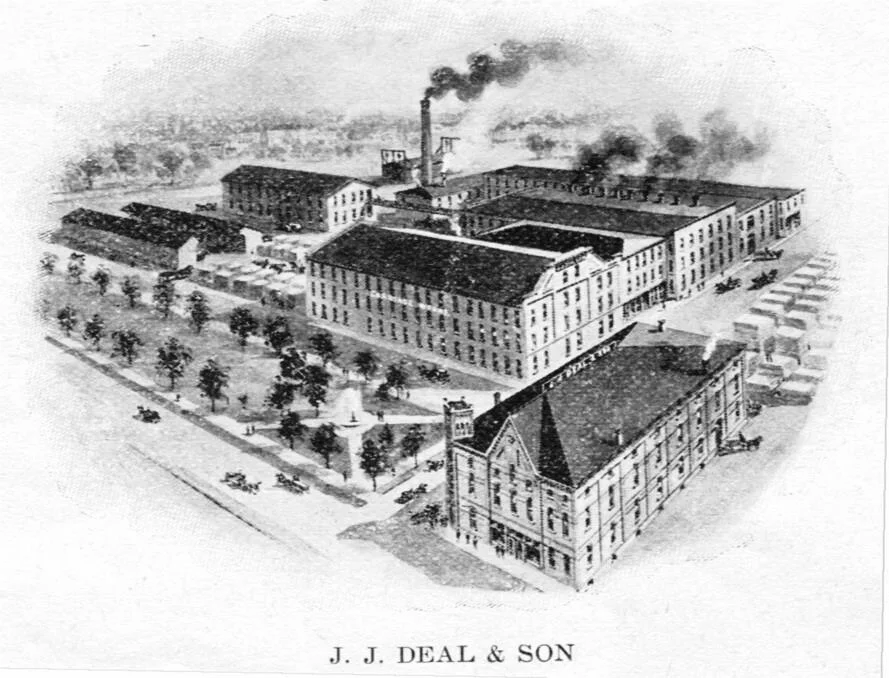

Jacob J. Deal came to Michigan from New York State in 1854 and finally settled in Jonesville in 1858. Originally a blacksmith, Jacob sold his shop in 1865, buying two small buildings on West Street, where he turned to building wagons and buggies. Jacob had the golden touch, eventually needing over a dozen employees. Numerous buggy-building businesses were established, but the Deal plant thrived while many others failed. The company built carts, wagons, carriages and sleighs of excellent quality. The use of lead paint—the norm for that time when its lethal consequences were unknown—assured that a few of these products remain in pristine condition to this day. The Hillsdale County Historical Society owns one of Jacob’s wagons.

When Jacob’s surviving son, George, became his partner in 1891, the business was renamed J.J. Deal and Son. George’s enthusiasm for the new horseless carriages, specifically delivery trucks, led to the company assembling “autobuggies.” These evolved into the Deal automobile in 1908. George died suddenly later that year, and without his leadership the company went out of business in 1915. Two known Deal autos still exist, one in the display window of the Jonesville City Office at East Chicago and Evans streets in Jonesville.

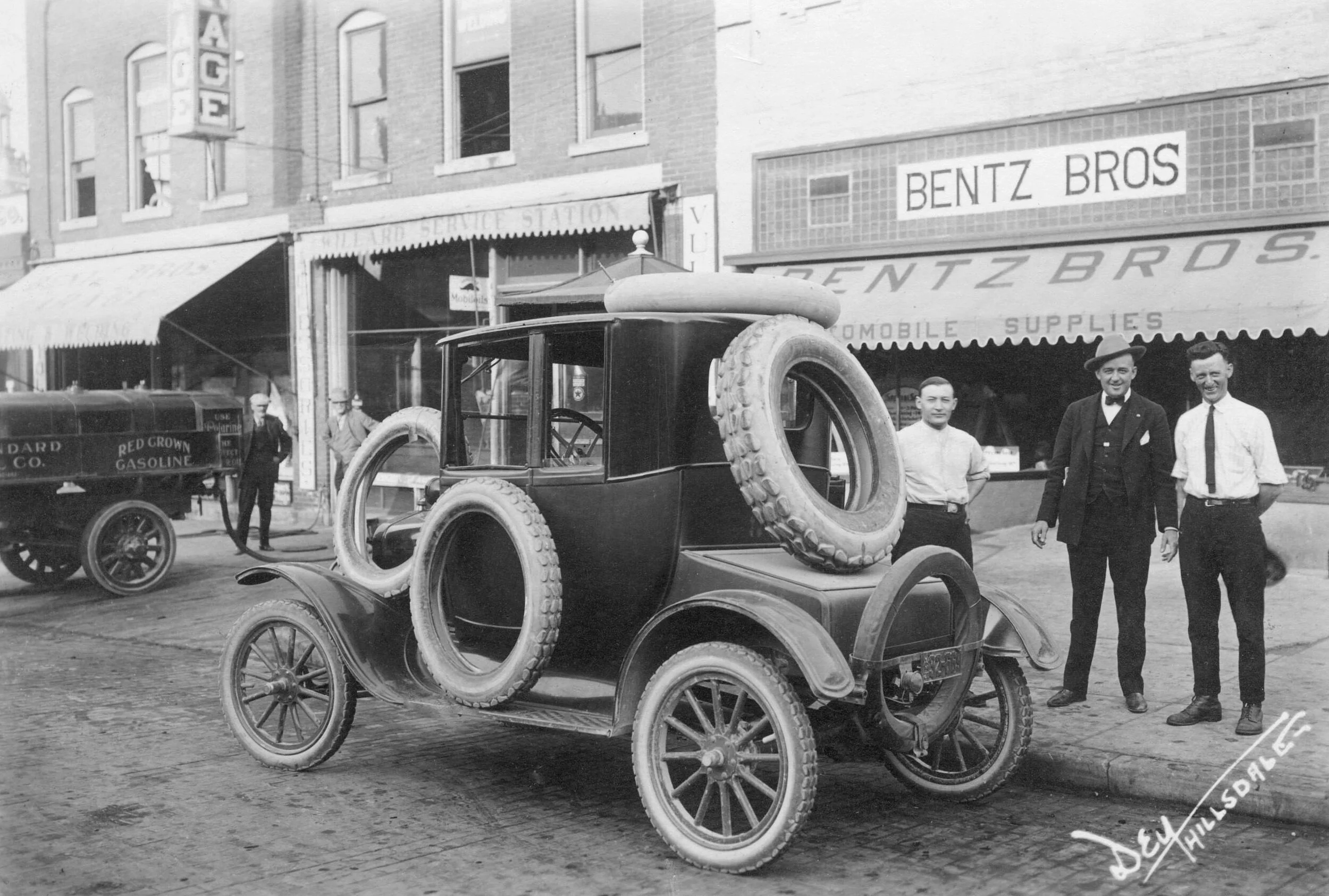

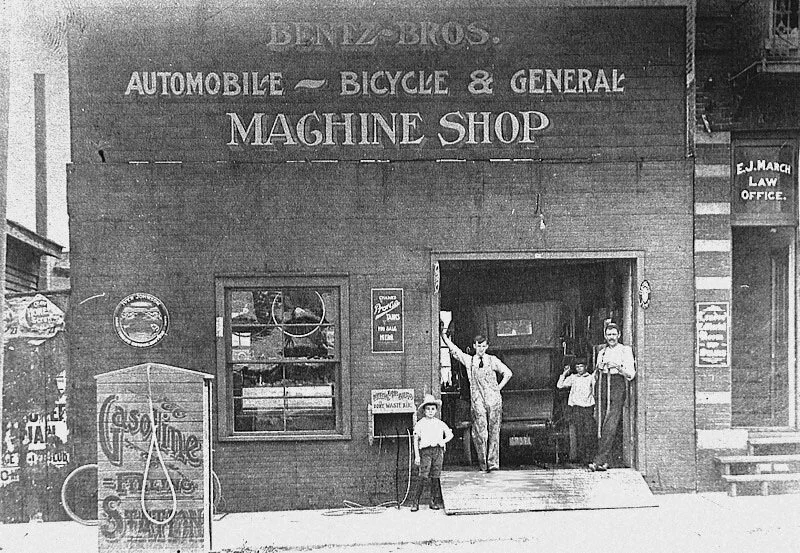

Livery stables were gradually replaced by bicycle, machine and automobile shops. Bentz Brothers, which offered all three services, received their automobiles in pieces. Men were employed to put them together, and occasionally lively competitions determined which crew could assemble a (working) car the fastest.

Bentz Brothers and Pinkham and Wright were two of the early car dealers in Hillsdale County. Like Bentz Brothers, Pinkham and Wright was originally located on Broad Street in Hillsdale. They moved twice, first to Railroad Street (now Carleton Road) and finally to McCollum Street. This last move raised the hackles of the local residents who fought the idea of a business invading their residential neighborhood. Pinkham and Wright prevailed in September 1919 after sentiment shifted. They built a brick building that went on to be Montgomery Ward and is now the Mid-Town Building.

Robert Simpson hedged his bets with his business, established in 1912. He originally provided a variety of services in an old blacksmith’s shop in Litchfield. His employees repaired farm machinery, bicycles, buggies and lawn movers as well as automobiles. It was a humble beginning for what would eventually become Simpson Industries, which made car parts, and later Game Time playground equipment.

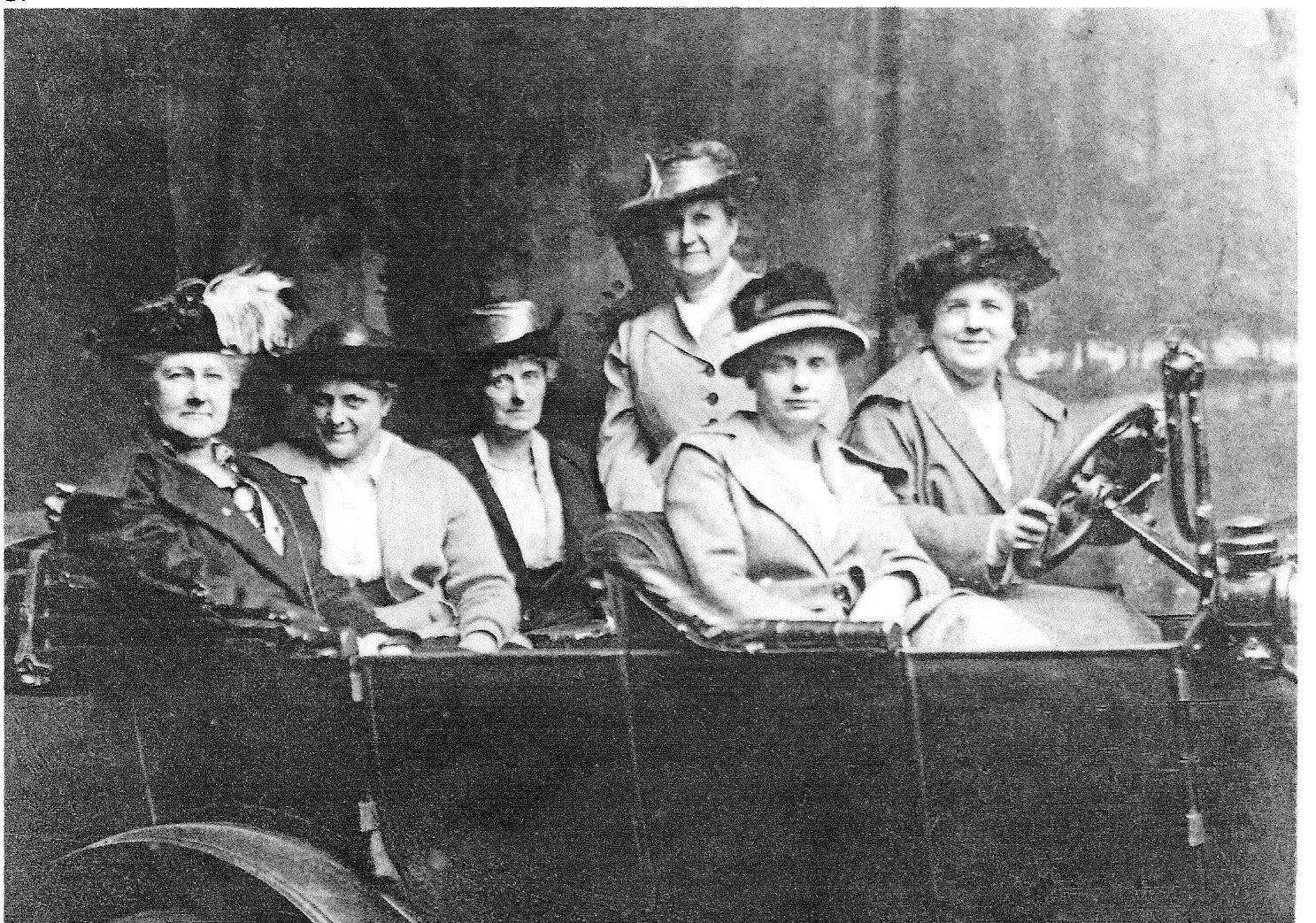

Given that the people who could afford the earliest cars could also afford specialized clothes to wear when driving them, the fashion industry seized the opportunity to benefit from the horseless carriage. The most obvious need was something to keep clothes clean when roaring along dirt roads at 15-25 mph. Most basic was the full-length, loose-cut cloth coat called a duster that was worn by both men and women. Those with more disposable income turned to a coat that ranged from a lightweight leather duster to a shaggy fur costume, depending on the weather. Driving coats for ladies were marketed in a variety of colors to match one’s automobile and were offered in fine materials such as linen and silk—with added weatherproofing if so ordered. Special driving gloves were a necessity. Finally, a driving cap for men often came with goggles attached to defend against dust and the occasional pebble. Women’s hats included removable dust shields to protect the wearer’s face.

knowles road gas station

Instead of feed and water, cars needed gasoline. Some of the early dealerships had their own gas pump in front of their business, but “filling stations” soon sprang up around the county. By the late 1920s houses were coming down and service stations going up. Most were mom-and-pop (or more accurately, pop) operations. The pumps were far more complex to operate than they are today, requiring an attendant with a strong arm who knew what he was doing. Each gasoline pump had a glass globe on top with a gravity feed. After ascertaining how much gas the customer wanted, the attendant pushed and pulled the crank on the pump to draw gas into the globe until it reached the line that matched the number of gallons desired. Then a hose attached to the globe was placed in the car’s gas tank and gravity did the rest. Eventually a mechanized pressure pump within the gas pump housing made getting fuel easier, but the customer was still taken care of royally. Each remained in his or her car as attendants, many teenage boys in their first jobs, emerged from the office. As the fuel was dispensed, the engine oil level was checked and the windows washed, all without extra charge.

With the growing prevalence of automobiles, national suppliers of petroleum turned to Madison Avenue to stimulate brand loyalty. Boiled down to basics, each company offered identical services at their stations. In Hillsdale County one to three bays for servicing cars were usual. Along with products for cars, the office stocked tobacco products, candy bars and an ice-filled cooler of Coke and Nehi beverages. Gas station offices also served as a social club for men with time on their hands. Women were generally expected to stay in their cars (and out of the men’s hair) under the guise that they deserved pampering by the attendants.

Many of the first horseless carriages were electric. The Stocks of Broad Street owned one that was used by Mrs. Wilhelmina Stock on her inspection tours of her park. When Henry Ford introduced the mass-produced and gas-powered Model T in 1908, however, the electric car was dealt a death blow. By 1912 a car fueled by leaded gas cost only $650, while the average electric roadster sold for $1,750. Despite the benefits of leaded gas to fuel efficiency and engine protection, in the 1970s the danger of lead emissions to the neurological systems of children led to the exclusive use of unleaded gasoline. Today global climate change, caused in large part by gasoline emissions, has brought us full circle back to electric cars and a future of all-electric vehicles.