The “Super Outbreak” of 1974: Tornadoes Damage Hillsdale County and the Eastern Half of the United States

The Most Outstanding Severe Convective Weather Episode on Record in the Continental United States

It was a mild start to the day in Hillsdale County on April 3, 1974, with an early morning temperature around 40 degrees following a day that had reached a high of 65 degrees; nearly 15 degrees above the historical average. The forecast was for temperatures around 60 degrees with showers and cloudy conditions in the Lower Peninsula, and rain and snow in the Upper Peninsula. Residents may have been a little uneasy, as an Enhanced Fujita 1 (EF1) tornado had tracked from southeast of Colon to Coldwater two days before, although no injuries had been reported from the narrow and short 10-mile stretch. This storm was part of a system that produced more than 20 tornadoes, primarily in Alabama and Mississippi, that had caused significant damage and three deaths.

On the evening of April 2, a surface low developed over eastern Colorado and moved quickly across Texas. Propelled by a strong upper jet stream, the cold front began mixing with moist tropical, unstable air over the Gulf States and Tennessee and pushed rapidly into the Ohio Valley. The clash of these air masses produced four bands of storms covering a devastating 24-hour period that has come to be known as the “Super Outbreak of 1974.”

According to Natural Disaster Survey Report 74-1 issued in December 1974 by the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “In terms of total number, path length and total damage, the massive tornado occurrence of April 3-4, 1974, was more extensive than all previously known outbreaks. Of the 127 tornadoes documented, 118 had paths over a mile long. The total paths amounted to 2,014 miles, resulting in 315 deaths. By comparison, during the Tri-State outbreak of March 18, 1925, seven tornadoes traveled 437 miles and caused 746 deaths. The Palm Sunday outbreak of April 11, 1965, spawned 31 tornadoes, which had paths totaling 853 miles, and killed 256.”

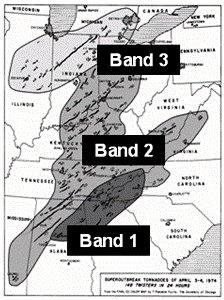

Although the first tornado touchdown was reported in Indiana around 9:30 a.m. CDT, the major tornadic activity occurred with bands two and three of the event, corresponding roughly from 2 p.m. and 10 p.m. on April 3. The bands and the tornadoes resulting from each are shown on the map below. Band 4, which ended the outbreak, did not produce any tornadoes and is not shown on the map.

The second band formed during the late morning of April 3 in NE Arkansas/SE Missouri and stretched into the Tennessee Valley. This band of storms was the longest-lived event and produced all of the F5 tornadoes and most of the F3 and F4 tornadoes. This band’s devastation included the cities of Depauw, Ind.; Brandenburg, Ky.; and Xenia, Ohio – all occurring within a two-hour period.

The third band produced the tornado having the longest track: the Monticello tornado, which was an F4 tornado that rocketed across Illinois and Indiana at ground speeds of 55 mph (nearly a mile a minute) and wind speeds of 166-200 mph, and stretched 110 miles with a path width of up to a half mile. This was the longest-tracked tornado during the Super Outbreak and accounted for 18 deaths, over 400 injuries and damage in excess of $100 million (1974 dollars). In the town of Monticello (in northern Indiana), the 630-foot, six-span Penn Central Railroad bridge was almost completely destroyed when four of the six spans, each weighing 115 tons, were lifted from the foundation and flung 40 feet into a nearby lake. Railroad ties, each weighing 250 pounds, were found in farm fields 10 miles from the bridge. Twenty additional tornadoes struck in 38 counties in Indiana, killing 47 and injuring nearly 900. One became an F5 in Southern Indiana, and two F4 tornadoes cut long swaths from Madison, Indiana to just west of Cincinnati.

Hillsdale County Tragedies

On the evening of April 3, most Hillsdale County residents had likely finished dinner and were finishing up chores or settling down to watch “Little House on the Prairie” or “Tony Orlando and Dawn,” as it was a Wednesday evening. They may have been uneasy, as a tornado watch had been issued at 6 p.m. And not long afterwards, the sirens would have wailed out the signature “tornado take cover” pattern that was feared by many (at that time, the “take cover” level was the most serious level; today “tornado warning” is our signal to seek strong shelter).

Around 8:30 p.m., strong winds roughed up small buildings and vegetation, and then-Director of Emergency Services William E. (Bud) Van Horn correctly noted that this damage was not due to tornadic winds, an observation later confirmed by the National Weather Service (NWS). This cell moved in a northeasterly direction into the City of Hillsdale, and Van Horn observed the next day that as his aerial survey approached the Mechanic Road and Lake Wilson Road area, tree tops showed evidence of twisting and rooftops had been blown off.

In a short time, at 8:44 p.m., the NWS confirmed that an F2 tornado landed in Riley’s Trailer Park on Hillsdale Road near Moore Road, northeast of the City of Hillsdale. Resident Francis Michael was hospitalized and his home was nearly destroyed. Several others were severely damaged, including that of Mr. and Mrs. Gobel Salyer, who managed to access the shelter of the park’s utility building just before the tornado struck. Of the 29 homes in the park, only nine were left undamaged. The park was owned by Mrs. Myrtle Riley and her son Elwyn, who lived south of the park. The first thing they saw that night were sparks from damaged power lines. When they left their house to see what was going on, Mrs. Riley said, “I had no idea until I went over there that it was so awful. I was just sick to my stomach.”

Within minutes, the tornado roared across Milnes Road, where the home of Ballard and Carolyn Holbrooks and their two young children was demolished. Tragically, Mr. and Mrs. Holbrooks did not survive the injuries they received during the event. After the tornado struck, the children made it to the home of a neighbor, where they were soon transferred by ambulance to the hospital. The children said they were told by their father “to lie down in the hallway floor,” and their parents then lay down on top of the children to protect them. In a strange twist, one of Mr. Holbrooks’ sisters is Mrs. Salyer, who had been away that evening and returned to her home at Riley’s Trailer Park to find just debris. She was not aware until later of the death of her brother Mr. Holbrooks. The Holbrooks children stayed first with another sister of Mr. Holbrooks, the John Wiremans of Jonesville, and later settled permanently with the Salyers. A former Hayes-Albion co-worker of Mr. Holbrooks started a fund for the children, noting that “Ballard was always good-natured and willing to help everybody.”

Four miles northeast, near Brown and Sterling roads, the dairy farm of the A.N. and Keith Brown family sustained a total loss of one barn and extensive damage to the milking parlor, delaying the morning milking. Mrs. A.N. Brown reported being unable to open the east-facing doors and windows in an effort to depressurize the house, but it was too late: the tornado blasted past with the signature sound of a freight train. A second barn, which was across the road and belonging to Mr. Tom Roberts, was also destroyed.

Also on Sterling Road was the farm of Mr. and Mrs. Simon Wagler. They had taken cover in their son’s basement, two miles away, then left for home when the all-clear signal was issued. However, just as they were leaving, a second take-cover command was issued and they headed back to the basement, just minutes before the tornado hit. Another relative’s home, which was close by, was completely demolished, and the Waglers lost part of their house as well as their barn and garage.

Northeast of Jerome, on Goose Lake, Richard Phillips was hospitalized after injuries sustained when a refrigerator fell through the floor of their home while they sought shelter in the basement.

The final fatality of the evening in Michigan occurred after the storms. As an employee of the Michigan Public Service Commission, Harold Dean Gardner of Litchfield was surveying the damage. He was heading west on Sterling Road when his vehicle hit a limb laying on the road, which then broke through the windshield and killed Mr. Gardner.

The twister stayed on the ground for 19.3 miles, finally dissipating just west of Clark Lake, near the intersection of US-127 and Jefferson Road. Hillsdale Community Health Center was fully staffed under a major disaster alert and treated 23 patients that evening who had storm-related injuries.

But this storm system was not yet finished with Michigan: At 9:15 p.m., a second tornado made landfall just inside the Hillsdale County border on US-127 at the west edge of Hudson. Three homes were destroyed, and the occupants of one, Mr. and Mrs. Galbreath, were injured. The other two homes were unoccupied at the time. This hit also damaged parts of two barns adjacent to the homes. Residents of Hudson had been advised to take cover at 6:30 p.m., but the order was lifted at 8:45, 30 minutes before the tornado touched down.

Aftermath – Local

The official NWS data puts the number of damaged structures in Hillsdale County at 160. Three people lost their lives and 23 were injured and treated at the Hillsdale Community Health Center (now Hillsdale Hospital). Power was out to thousands of residents, but many areas were restored by 9 a.m. the following morning, and nearly all would be back in service by that evening, due to the efforts of Consumers Power Company (the name of Consumers Energy at the time) and Hillsdale Board of Public Works crews. A representative of the Michigan Bell Telephone Company noted that the only major issue with telephone service was the difficulty in “getting an open circuit. They are very very busy, and it’s just a matter of being patient and keep trying,” he said.

Several agencies were instrumental in the area’s recovery. The local Civil Defense chapter was vital in its role in providing in-person weather reports to the command post, including reports of tornadoes spotted. The American Red Cross set up stations around the county, including at Riley’s Trailer Park, supplying disbursement checks to certain stores, food and clothing to victims. The Hillsdale McDonald’s restaurant sent a bus to Riley’s and the Goose Lake area with coffee and food for the residents. Police, fire, hospital and public works employees spent countless hours restoring infrastructure and caring for residents. Bud Van Horn also credited the Salvation Army, area churches and area heavy equipment contractors for donating time and equipment for the cleanup. The county was declared on April 5 to be a disaster area by Van Horn. He estimated that the damage loss was at least $3.5 million.

Aftermath – National

The “Super Outbreak of 1974” stretched over 13 states, and produced 148 tornadoes in a 24-hour period, 30 of which registered as F4 or F5 in intensity. Ultimately, the storms killed 335 people and injured over 6,000. The total path length was more than 2,500 miles. The damage estimate was $4.5 billion in 2019 dollars, and 10 states were declared federal disaster areas. Until the 2011 tornado outbreak, it was the largest outbreak of tornadoes in U.S. recorded history.

An analysis of the event in the American Meteorology Society Journal in 2010 by Corfidi et al noted that “entire years noted for their prominent tornado counts (e.g., 1947, 1953 and 2003) pale in comparison to the 18-hour period that began around midday on Wednesday, 3 April 1974. Twenty-five F3 or greater long-track {more than 40 km (25 mi)} tornadoes occurred during the same period, more than triple the annual average of such events since 1880.” The authors’ meteorological analysis concluded that “… a combination of well-known ingredients occasionally can synergistically interact to yield an exceedingly rare event.”

Although NWS offices did a remarkable job in warning residents, in 1974, not all offices were equipped with radar, and even those that did had rudimentary tools for using the radar data to forecast, having to trace the data onto thin paper maps to determine the paths of the storms. Meteorologists relied on their ability to identify “hook echoes” in the data and on-the-ground spotters to issue the tornado warnings.

This outbreak spurred various agencies and universities to develop better diagnostic tools; that, coupled with the advent of faster computers, has resulted in greater lead times for warnings.

Marsha Layman 2024