The First Travelers to Hillsdale County

With the completion of the Erie Canal in 1821, travel to the “west” of the fledgling United States became considerably easier. Shallow canal boats, pulled by mules, crossed the Appalachian Mountains in a series of locks and viaducts to negotiate the 568-foot rise from the Hudson River to Lake Erie. Originally derided by many as “Clinton’s Big Ditch” after New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, who broke ground for the project in 1817, the Erie Canal was a marvel of engineering that allowed relatively easy two-way transportation of goods and people.

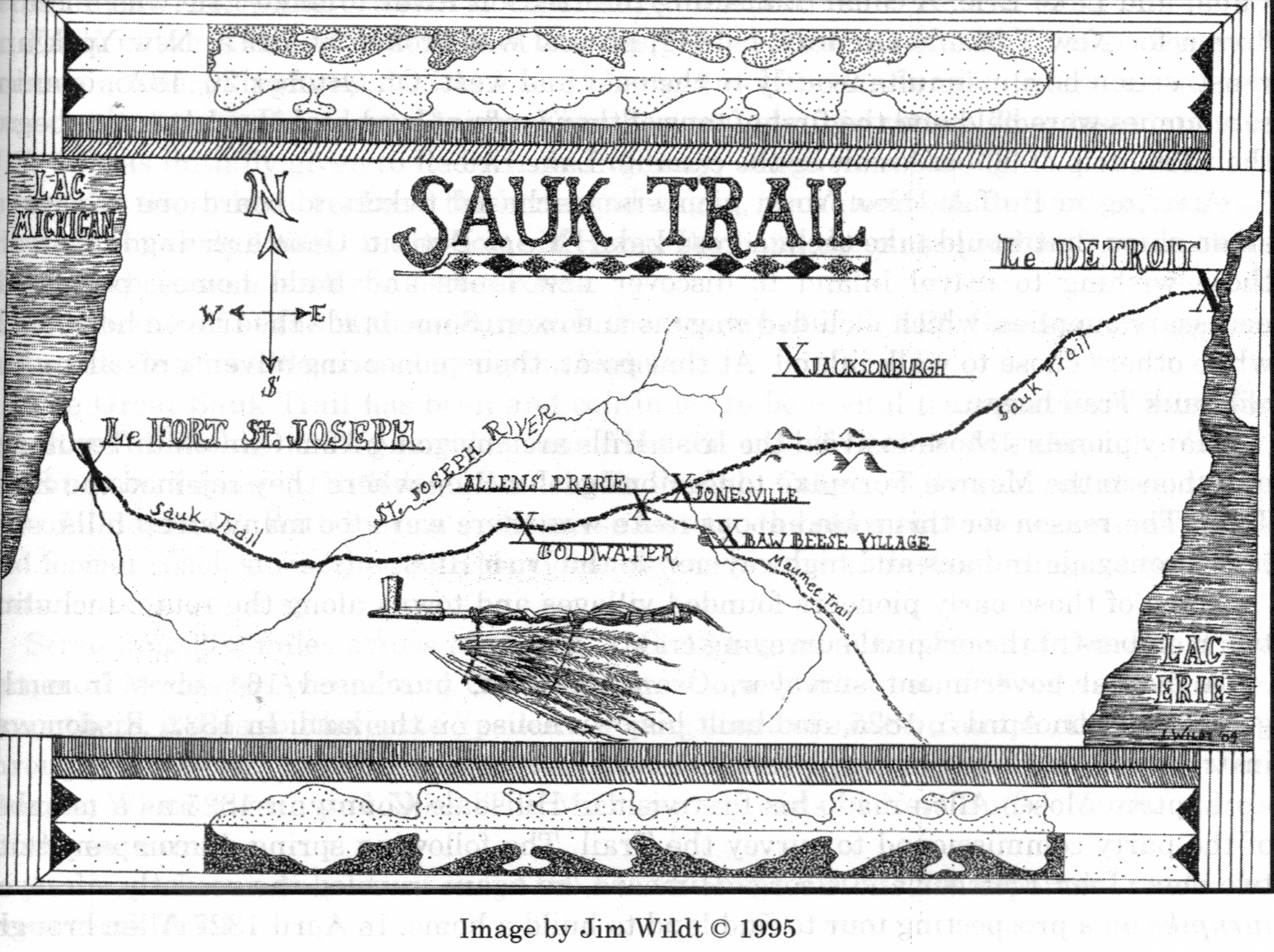

Arriving in Detroit at the western end of Lake Erie, travelers confronted the forested wilderness of the Northwest Territory. Many of those headed west through Michigan Territory followed the Sauk Trail, which had been a travel way for the Potawatomi Indians for hundreds of years. Anxious to populate the Territory with white settlers, the federal government made treaties with the Potawatomi, “buying” their land for insignificant compensation and then selling it at low prices to pioneers wanting to settle in the newly opened land.

The Sauk Trail was widened to 100 feet by the federal government and renamed the Chicago Military Road. In 1827 the first white family, that of Moses and Mary Allen, traveled along the Chicago Road to Lenawee County. (This area became Vance Township in 1829 and was renamed Hillsdale County in 1834.) Captain Allen, a veteran of the War of 1812, was part of the survey crew that first laid out the route of the Chicago Road. The Allen family initially lived in a French trapper’s abandoned cabin at the juncture of the current US-12 (which loosely follows the Sauk Trail) and M-49. The next year the family of Beniah and Lois Jones traveled along the Chicago Road. They lived in the Allens’ grain shack before moving to their own cabin on the St. Joseph River in what would become Jonesville.

The proven success of the Erie Canal inspired Stevens T. Mason, Michigan’s first governor after it achieved statehood in 1837, to follow DeWitt Clinton’s lead in creating a water route to make travel easier. In addition to three railroads, Mason envisioned two canals spanning Michigan. One was the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal, which was supposed to connect Lake St. Clair with Lake Michigan. Neither it nor the other waterway was completed, however, and travel across Michigan remained on solid ground. The Chicago Road made wagon travel manageable and a daily stagecoach run between Detroit and Chicago possible.

The trickle of new settlers to Michigan—and Hillsdale County—became a steady stream.